6 An electrical diagram told the young researchers where to place each of the kit’s parts on the circuit board. The students had to make sure they connected some pieces to the circuit board in the right direction. If any of these went in backward, the radio might not work. Or worse. If the parts were assembled incorrectly, the electric current might damage the radio’s parts.

7 The do-it-yourself kits included diodes. These work like one-way gates for an electric current. On each diode, a black band denoted its negative end, or cathode. To work properly, it had to go into a hole marked with a vertical line on the electrical diagram.

8 Additional parts perform other jobs. Those functions make electronic circuits work in radios—and lots of other electronic devices. Resistors, for instance, reduce the flow of current. And capacitors (kuh-PASS-it-terz) temporarily store energy.

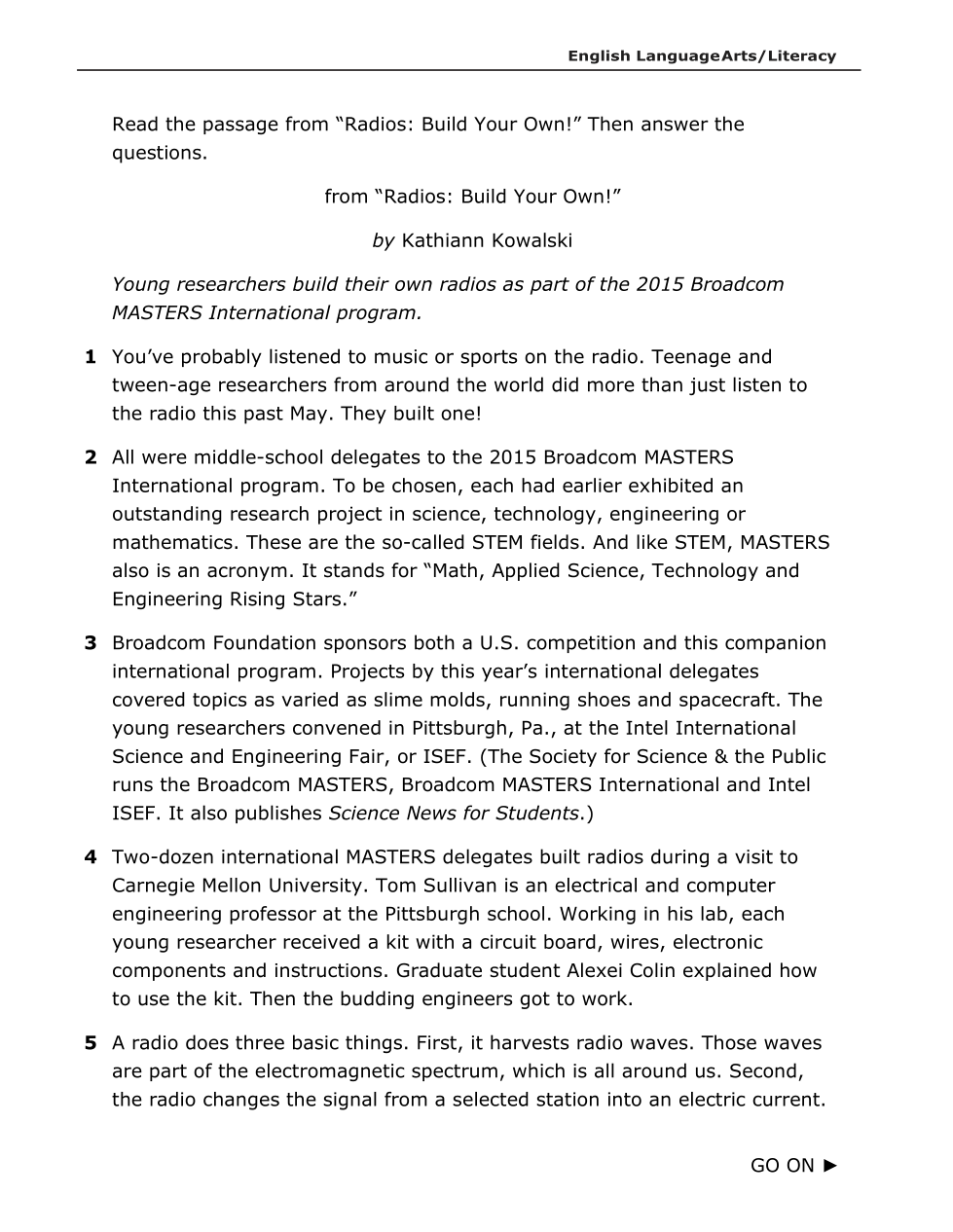

9 The radio’s pieces didn’t just snap into place. Each had to be soldered (SAAH-derd) to the circuit board. Solder is a metal that melts easily. It is used to join together metal pieces. To attach a component to the circuit board, the students used a device called a soldering iron, which preheats parts to be joined. They also added a bit of a gooey compound. Then they melted a bit of solder between the parts. The rosin-based goo, called flux, helped the solder flow around the hole in the circuit board where the piece was to be joined. This ensured a good contact.

10 The students patiently soldered parts in place. Even so, the process was sometimes tricky. “Trying not to burn myself was really hard,” noted 13- year-old Isabella O’Brien of Canada.

11 Getting everything into place at the same time got awkward, too. “I had a couple of parts that weren’t physically touching the board,” says 13-year�old Raghav Ganesh of San Jose, Calif. “It’s like you needed some sort of third arm to make it easier.” Without physical contact, current can’t flow through the radio within a closed circuit. In other words: The radio wouldn’t work.