Metí algunas cosas en una bolsa, llamé a la empresa para decirles que no iría y me subí a un tren hacia mi antigua ciudad natal.

No encontré el mismo pequeño y tranquilo pueblo costero que recordaba. En las cercanías había surgido una ciudad industrial durante el rápido desarrollo de los años sesenta, lo que provocó grandes cambios en el paisaje. La única pequeña tienda de regalos junto a la estación se había convertido en un centro comercial y el único cine de la ciudad se había convertido en un supermercado. Mi casa ya no estaba. Había sido demolido unos meses antes, dejando sólo un rasguño en el suelo. Todos los árboles del jardín habían sido talados y parches de maleza cubrían la negra extensión de terreno. La antigua casa de K. también había desaparecido, en su lugar había un aparcamiento de hormigón lleno de coches y furgonetas de viajeros. No es que me sintiera abrumado por el sentimiento. El pueblo había dejado de ser mío hacía mucho tiempo.

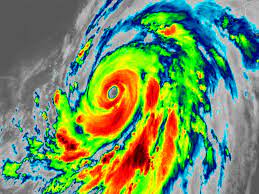

Bajé hasta la orilla y subí las escaleras del rompeolas. Del otro lado, como siempre, el océano se extendía a lo lejos, sin obstáculos, enorme, el horizonte una única línea recta. La costa también tenía el mismo aspecto que antes: la larga playa, las olas rompiendo, la gente paseando a la orilla del agua. Eran más de las cuatro y el suave sol del final de la tarde abrazaba todo lo que había debajo mientras comenzaba su largo, casi meditativo, descenso hacia el oeste. Dejé mi bolso en la arena y me senté junto a él para apreciar en silencio el suave paisaje marino. Al mirar esta escena, era imposible imaginar que un gran tifón alguna vez había arrasado aquí, que una ola enorme se había tragado a mi mejor amigo en todo el mundo. Seguramente ya casi no quedaba nadie que recordara aquellos terribles acontecimientos. Empecé a parecer como si todo fuera una ilusión que yo había soñado con vívidos detalles.

Y entonces me di cuenta de que la profunda oscuridad dentro de mí se había desvanecido. De repente. Tan repentinamente como había llegado. Me levanté de la arena y, sin molestarme en quitarme los zapatos ni arremangarme los puños, caminé hacia las olas para dejar que las olas me acariciaran los tobillos.

Casi en reconciliación, al parecer, las mismas olas que habían llegado a la playa cuando yo era niño ahora me lavaban los pies con cariño, empapando de negro mis zapatos y las perneras de los pantalones. Habría una ola que se movía lentamente, luego una larga pausa y luego otra ola iba y venía. La gente que pasaba me miraba de forma extraña, pero no me importaba.

Miré hacia el cielo. Unos cuantos trozos de nubes de algodón gris colgaban allí, inmóviles. Parecían estar ahí para mí, aunque no estoy seguro de por qué me sentí así. Recordé haber mirado así al cielo en busca del “ojo” del tifón. Y entonces, dentro de mí, el eje del tiempo dio un gran impulso. Cuarenta largos años se derrumbaron como una casa en ruinas, mezclando tiempos antiguos y nuevos en una sola masa arremolinada. Todos los sonidos se desvanecieron y la luz a mi alrededor se estremeció. Perdí el equilibrio y caí a las olas. Mi corazón latía en el fondo de mi garganta y mis brazos y piernas perdieron toda sensación. Permanecí así durante mucho tiempo, con la cara en el agua, incapaz de mantenerme en pie. Pero no tuve miedo. No, en absoluto. Ya no había nada que temer. Esos días ya habían pasado.

Dejé de tener mis terribles pesadillas. Ya no me despierto gritando en mitad de la noche. Y ahora estoy intentando empezar la vida de nuevo. No, sé que probablemente sea demasiado tarde para empezar de nuevo. Puede que no me quede mucho tiempo de vida. Pero incluso si llega demasiado tarde, estoy agradecido de que, al final, pude lograr una especie de salvación, de efectuar algún tipo de recuperación. Sí, agradecido: podría haber llegado al final de mi vida sin salvarme, todavía gritando en la oscuridad, asustado.

El séptimo hombre guardó silencio y volvió su mirada hacia cada uno de los demás. Nadie hablaba ni se movía ni siquiera parecía respirar. Todos estaban esperando el resto de su historia. Afuera, el viento había amainado y nada se movía. El séptimo hombre volvió a llevarse la mano al cuello, como si buscara palabras.

“Nos dicen que lo único que tenemos que temer es el miedo mismo; pero no lo creo”, dijo. Luego, un momento después, añadió: “Oh, el miedo está ahí, está bien. Nos llega de muchas formas diferentes, en momentos diferentes, y nos abruma. Pero lo más aterrador que podemos hacer en esos momentos es darle la espalda, cerrar los ojos. Entonces tomamos lo más preciado que llevamos dentro y se lo entregamos a otra cosa. En mi caso, ese algo fue la ola”.