In this passage from a book about the sinking of the Titanic, the author describes the ship’s amenities and safety precautions—and why so many people couldn’t escape on lifeboats.

Introduction from Sinking of the “Titanic” Most Appalling Ocean Horror

Author: Jay Henry Mowbray, Ph.D., LL.D

Publisher: The Minter Company, Harrisburg, PA

Published: 1912

1 The human imagination is unequal to the reconstruction of the appalling scene of the disaster in the North Atlantic. No picture of the pen or of the painter’s brush can adequately represent the magnitude of the calamity that has made the whole world kin.

2 How trivial in such an hour seem the ordinary affairs of civilized mankind—the minor ramifications of politics, the frenetic rivalry of candidates, the haggle of stock speculators. We are suddenly, by an awful visitation, made to see our human transactions in their true perspective, as small as they really are.

3 Man’s pride is profoundly humbled: he must confess that the victory this time has gone to the blind, inexorable forces of nature, except in so far as the manifestation of the heroic virtues is concerned.

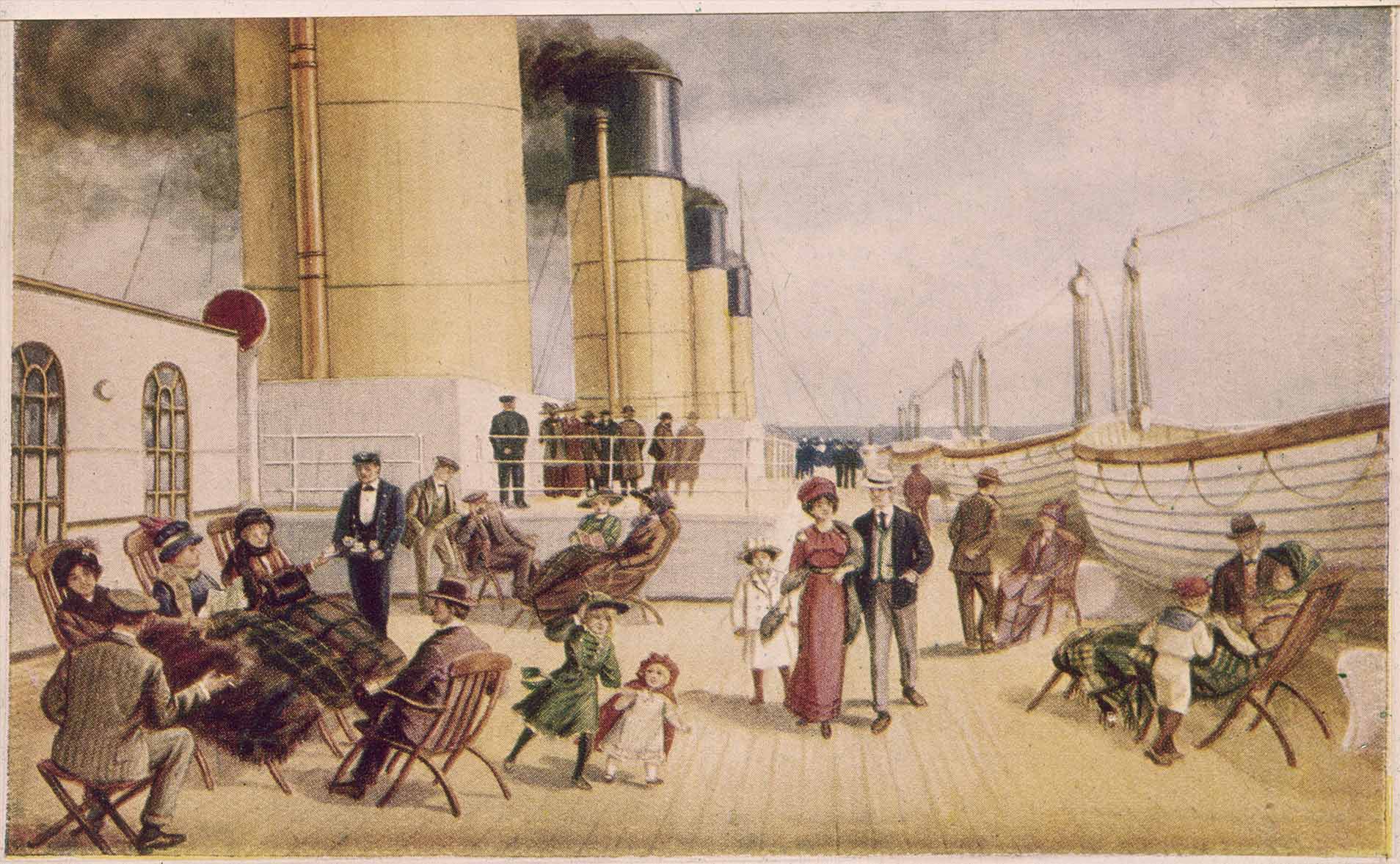

4 The ship that went to her final resting place two miles below the placid, unconfessing level of the sea represented all that science and art knew how to contribute to the expedition of traffic, to the comfort and enjoyment of voyagers.

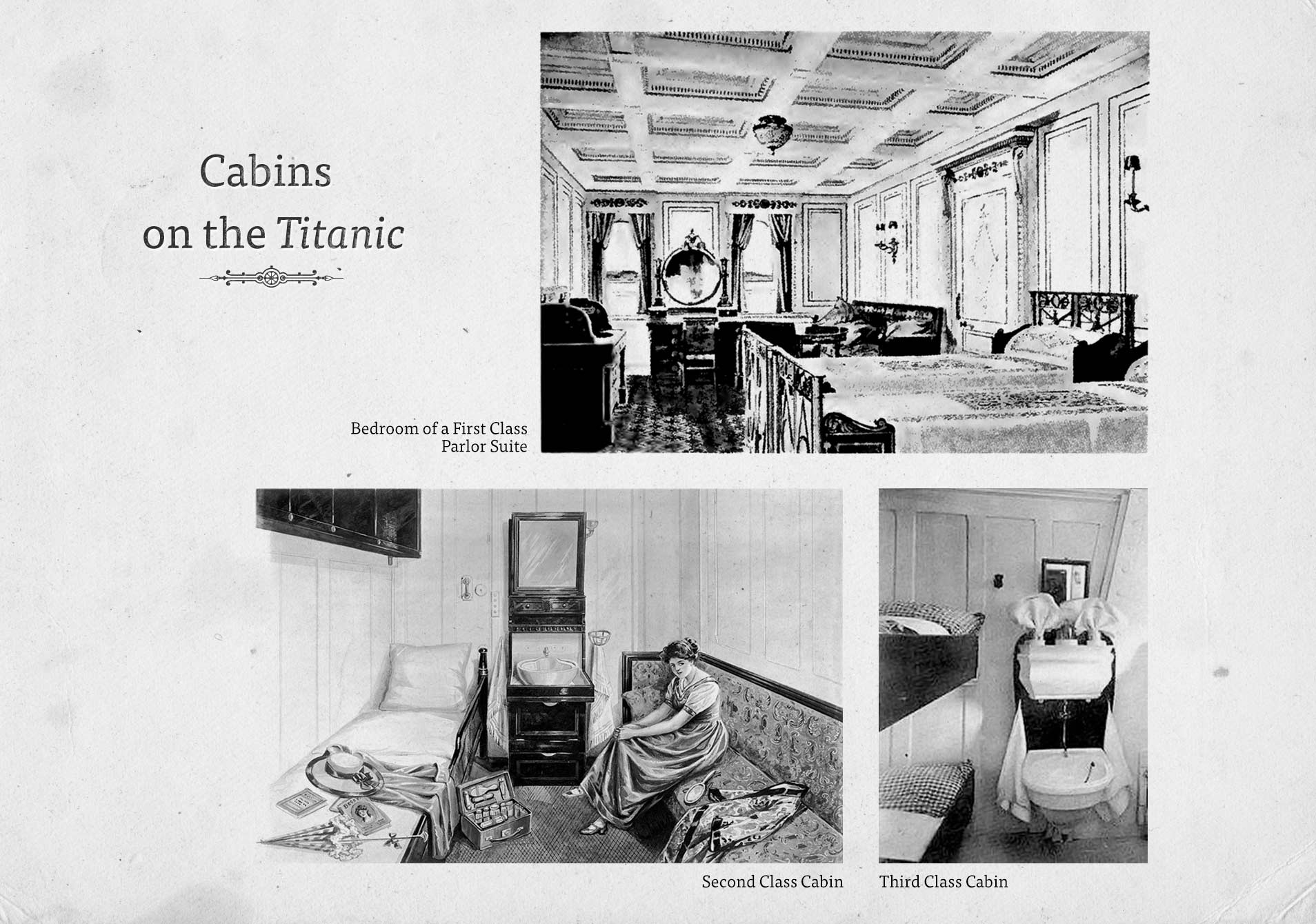

5 She had 15 watertight steel compartments supposed to render her unsinkable. She was possessed of submarine signals with microphones, to tell the bridge by means of wires when shore or ship or any other object was at hand.

6 There was a collision bulkhead to safeguard the ship against the invasion of water amidships should the bow be torn away. In a word, the boat was as safe and sound as the shipbuilder could make it.

7 It was the pride of the owners and the commander that what has happened could not possibly occur. And yet the Titanic went down, and carried to their doom hundreds of passengers and men who intimately knew the sea and had faced every peril that the navigator meets.

8 In the hours between half-past 10 on Sunday night and half-past 2 Monday morning, while the ship still floated, what did the luxuries of their $10,000,000 castle on the ocean avail those who trod the eight steel decks, not knowing at what moment the whole glittering fabric might plunge with them—as it did plunge—to the unplumbed abyss below?

9 What was it, in those agonizing hours, to the men who remained aboard, or to the women and children placed in the boats, that there were three electric elevators, squash courts and Turkish baths, a hospital with an operating room, private promenade decks and Renaissance cabins? What is it to a man about to die to know that there is at hand a palm garden or a darkroom for photography, or the tapestry of an English castle or a dinner service of 10,000 pieces of silver and gold?

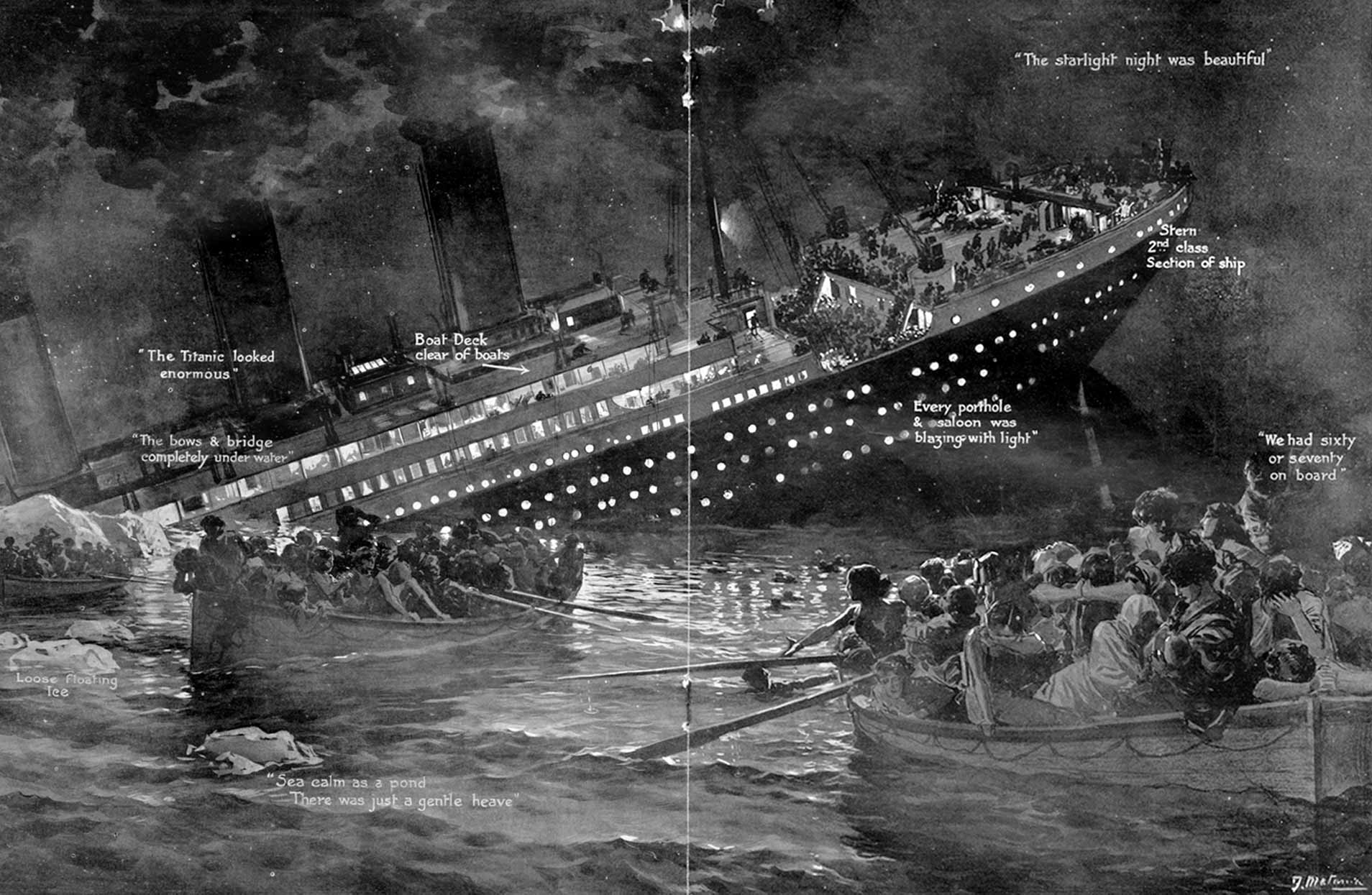

10 In that midnight crisis the one thing needful was not provided, where everything was supplied. The one inadequacy was—the lack of lifeboats.

11 In the supreme confidence of the tacit assumption that they never would be needed, the means of rescue—except in a pitiably meagre insufficiency—was not at hand. There were apparently but 20 boats and rafts available, each capable of sustaining at most 60 persons.

12 Yet the ship was built to carry 2435 passengers and 860 in the crew—a total of 3295 persons.

13 Whatever the luxuriousness of the appointments, the magnificence of the carvings and the paintings that surfeited the eye, the amplitude of the space allotted for the promenade, it seems incredible no calculation was made for the rescue of at least 2000 of the possible floating population of the Titanic.

14 The result of the tragedy must be that aroused public opinion will compel the formulation of new and drastic regulations, alike by the British Board of Trade and by the Federal authorities, providing not merely for the adequate equipment of every ship with salvatory apparatus but for rigorous periodical inspection of the appliances and a constant drill of the crew.

15 Let there be an end of boasting about the supremacy of man to the immitigable laws and forces of nature. Let the grief of mankind be assuaged not in idle lamentation but in amelioration of the conditions that brought about the saddest episode in the history of ships at sea.

16 The particular line that owned and sent forth the vessel that has perished has been no more to blame than others that similarly ignored elemental precautions in favor of superfluous comforts, in a false sense of security.

17 When the last boatload of priceless human life swung away from the davits of the Titanic, it left behind on the decks of the doomed ship hundreds of men who knew that the vessel’s mortal wound spelt Death for them also. But no cravens these men who went to their nameless graves, nor scourged as the galley slave to his dungeon.

18 Called suddenly from the ordinary pleasure of ship life and fancied security, they were in a moment confronted With the direct peril of the sea, and the absolute certainty that, while some could go to safety, many must remain.

19 It was the supreme test, for if a man lose his life he loses all. But, had the grim alternative thought to mock the cowardice of the breed, it was doomed to disappointment.

20 Silently these men stood aside. “Women first,” the inexorable law of the sea, which one disobeys only to court everlasting ignominy, undoubtedly had no place in their minds. “Women first,” the common law of humanity, born of chivalry and the nobler spirit of self-sacrifice, prevailed.

21 They simply stood aside.

22 The first blush of poignant grief will pass from those who survive and were bereft. But always will they sense in its fullest meaning this greatest of all sacrifice. Ever must it remain as a reassuring knowledge of the love, and faithfulness, and courage, of the Man, and of his care for the weak.

23 “Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friend.”