Excerpt: “California Culinary Experiences” from The Overland Monthly

Author: Prentice Mulford

Published: 1869 (public domain)

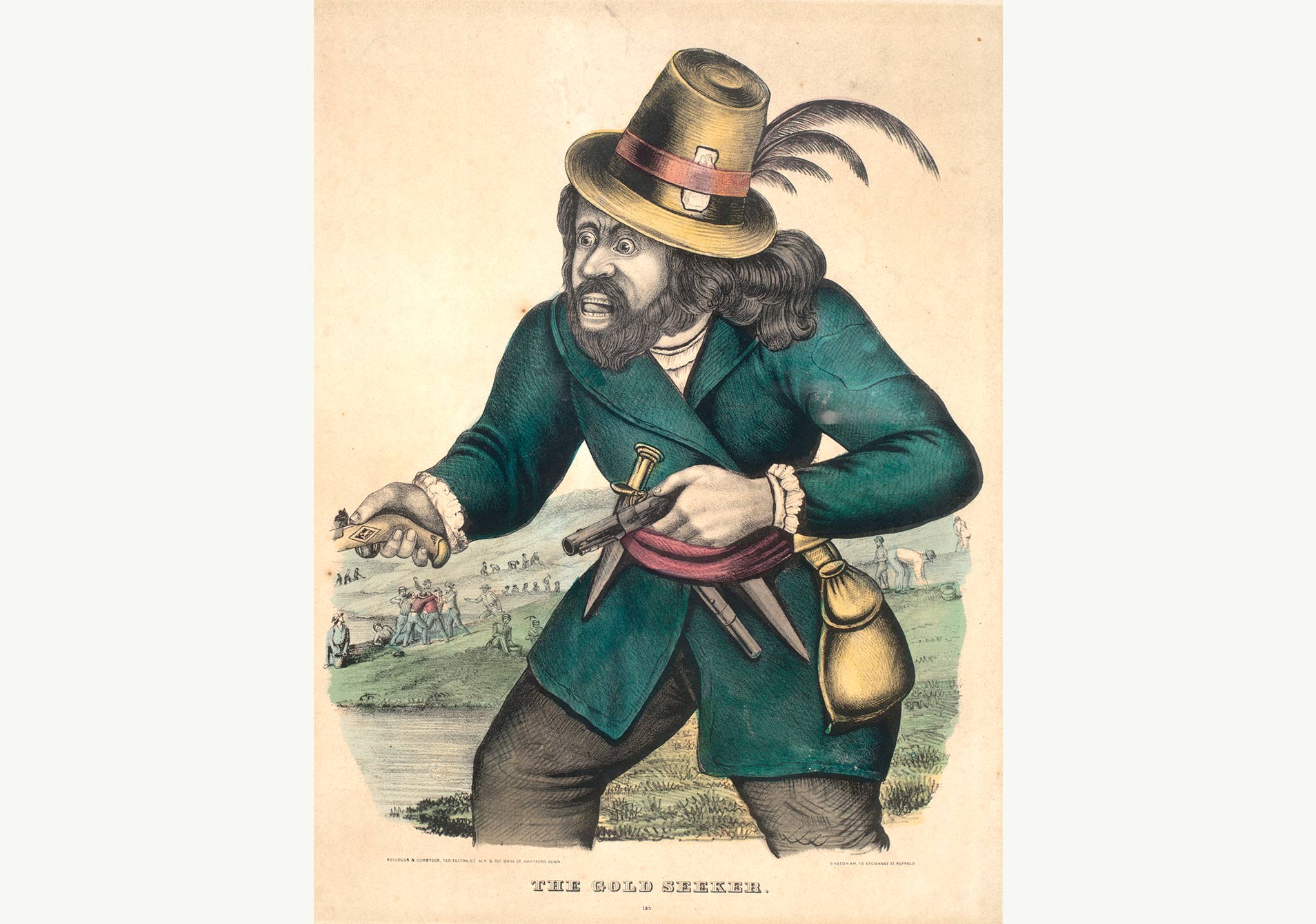

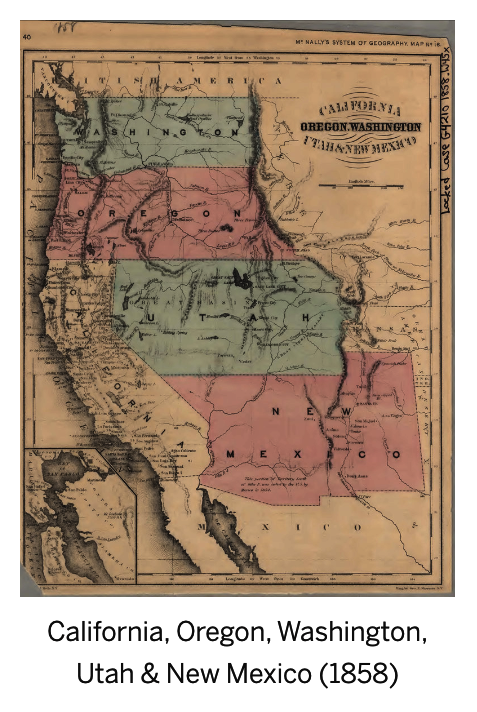

1 I am a survivor of all the different eras of California amateur cookery. The human avalanche precipitated on these shores in the rush of “49” and “50” was a mass of culinary ignorance. Cooking had always by us been deemed a part of woman’s kingdom. We knew that bread was made of flour, and for the most part so made by woman. It was as natural that it should be made by them as that the sun should shine. Of the knowledge, skill, patience and experience required to conduct this and other culinary operations, we realized nothing. So when the first—the pork, bean and flapjack—era commenced, thousands of us boiled our pork and beans together an equal period of time, and then wondered at the mysterious hardness of the nutritious vegetable. In the fall of “50” a useful scrap of wisdom was disseminated from Siskiyou to Fresno. It was that beans must be soaked over night and boiled at least two hours before the insertion of the pork. And many a man of mark to-day never experienced a more cheerful thrill of combined pride and pleasure, than when first he successfully accomplished the feat of turning a flap-jack.

2 We soon tired of wheat cakes. Then commenced the bread era; the heavy bread era, which tried the stomach of California. That organ sustained a daily attack of leaden flour and doubtful pork. The climate was censured for a mortality which then prevailed, due, in great measure, to this dreadful diet. With the large majority of our amateur cooks, bread-making proved but a series of disastrous failures. Good bread makers, male or female, are born, not made. In flour we floundered from the extreme of lightness to that of heaviness. We produced in our loaves every shade of sourness and every tint of orange, from excess of salæratus. Our crust, in varying degrees of hardness and thickness, well illustrated the stratifications of the earth. Our loaves “did” in spots. Much prospecting was often necessary to develop pay-bread.

3 In the early portion of “51,” just preceding the pie period, came an epoch of stewed dried apples. Even now, my stomachic soul shudders as I recall that trying time. After we had apple-sauced ourselves to satiety, with diabolical ingenuity we served it up to each other, hidden in thick, heavy ramparts of flour. It was a desperate struggle with duff and dumplings . . . I can now recall no living comrade of the dried apple era.

4 But those who first ventured on pies were men possessed in some degree of taste and refinement. No coarser nature ever troubled itself with pie-making. The preparation and seasoning of the mince meat, the rolling out and manipulation of the crusts, their proper adjustment to the plate, the ornamental scollops around the edge, (made with the thumb) and the regulation of the oven’s heat to secure that rich shade of brown, required patience and artistic skill.

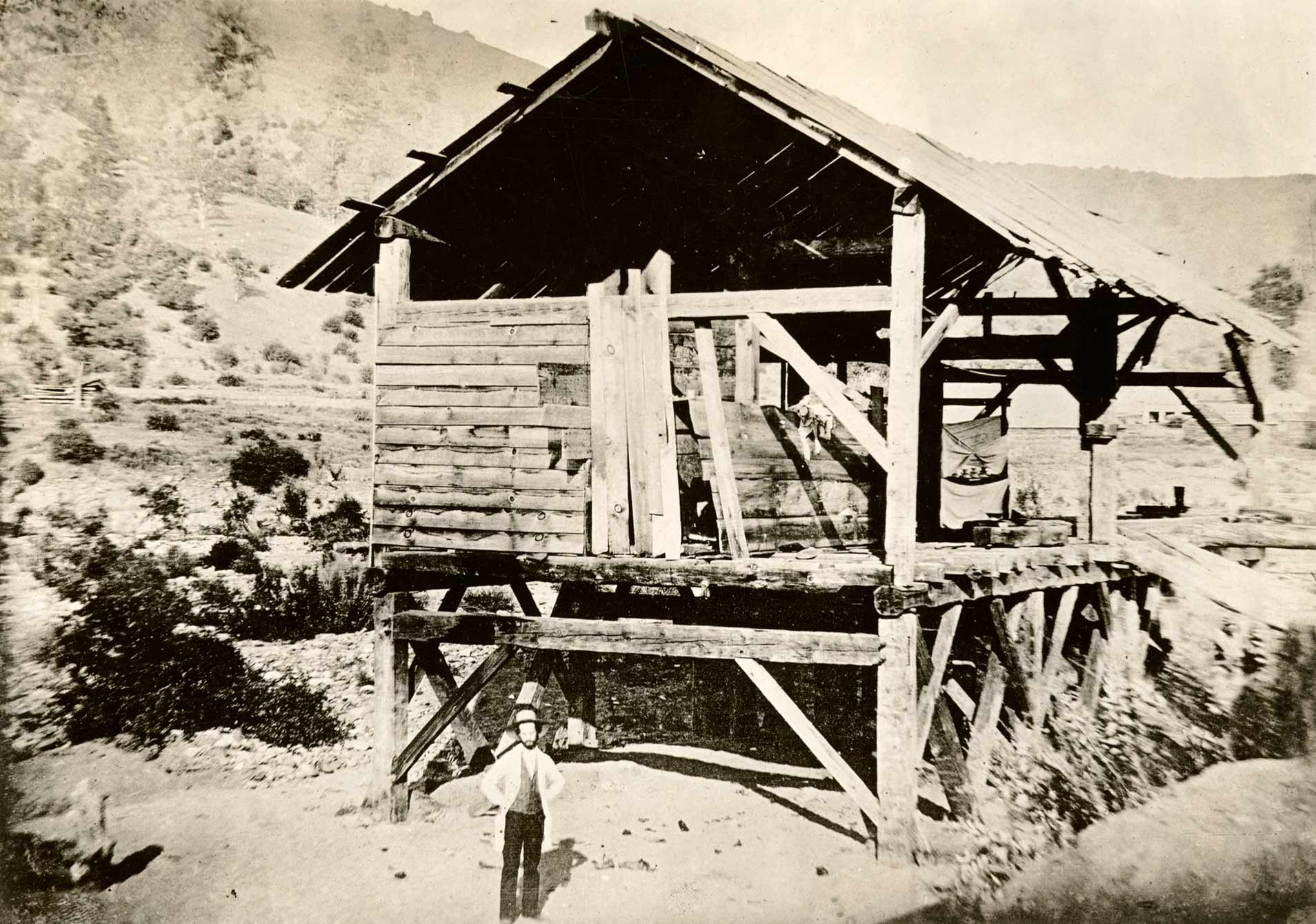

5 The early pie-makers of our State were men who as soon as possible slept in sheets instead of blankets, who were skilled in washing linen, who went in clean attire on Sundays, and who subscribed for magazines and newspapers. On remote bars and gulches such men have kept households of incredible neatness, their cabins sheltered under the evergreen oak, with clear rivulets from the mountain gorges running past the door, with clothes-lines precisely hung with shirts and sheets, with gauze-covered meat safe hoisted high in the branches of the overshadowing trees, protecting those pies from intruding and omniverous ground squirrels and inquisitive yellow-jackets; while about their doorway the hard, clean-swept red earth resembled a well-worn brick pavement. There is morality in pies.

6 There was a canned provision era, fruitful in sardines and oysters. The canned oysters of those days were as destructive as cannister shot. They penetrated everywhere. In remote and seldom-visited valleys of the Sierras, I have grown solemn over the supposition that mine were the first footsteps which had ever indented the soil. And then I have turned but to behold the gaping, ripped and jagged mouth of one of those inevitable tin cylinders scattered like dew over the land, and labelled “Cove Oysters.” One of our prominent officials, giving evidence in a suit relative to the disputed possession of a mining claim in a remote district, when asked what, in the absence of a house or shaft, he would consider to be indications of the former presence of miners, answered: “Empty oyster cans and empty bottles.”

7 I am a survivor of all the different eras of California amateur cookery. The human avalanche that fell on these shores in the gold rush of “49” and “50” was a mass of culinary ignorance. We knew that bread was made of flour, and that it was so made by women. It was as natural that it should be made by them as that the sun should shine. We realized nothing of the knowledge, skill, patience and experience required for this and other culinary operations. So when the first “pork, bean and flapjack” era began, thousands of us boiled our pork and beans together for the same length of time, and then wondered at the mysterious hardness of the nutritious vegetable. In the fall of “50” a useful scrap of wisdom spread from Siskiyou to Fresno: that the beans must be soaked overnight and boiled at least two hours before adding the pork. And a man never experienced a more cheerful thrill than when he first successfully accomplished the feat of turning a flapjack.

8 However, we soon tired of wheat cakes. Next came the heavy bread era, which strained the stomach of California. For most of our amateur cooks, bread-making proved a series of disastrous failures. Good bread makers, male or female, are born, not made. In flour we floundered from the extreme of lightness to that of heaviness. We produced in our loaves every shade of sourness and every tint of orange, from too much baking soda. Our crust, in varying degrees of hardness and thickness, resembled the layers of the earth. Much prospecting was often necessary to develop “pay bread.”

9 Early in “51,” just before the pie period, came an epoch of stewed dried apples. Even now, my stomach’s soul shudders as I recall that trying time. After we had apple-sauced ourselves to fullness, we served it up, hidden in thick, heavy walls of flour. It was a desperate struggle with duff [flour pudding] and dumplings. I can’t think of anyone who survived the dried apple era.

10 Those who first tried pie making were men with some degree of taste and refinement. Patience and artistic skill were required for the preparation and seasoning of the mincemeat, the rolling out of the crusts, their proper placement on the plate, the ornamental indents (made with the thumb) around the edge, and the regulation of the oven’s heat to produce that rich shade of brown. The early pie makers of our state were men who as soon as possible slept in sheets instead of blankets, who were skilled at washing linen, who wore clean attire on Sundays, and who subscribed to magazines and newspapers. On remote sandbars and gulches such men kept households of incredible neatness, their cabins sheltered under the evergreen oak, their clotheslines precisely hung with shirts and sheets, their meat pies hung safely in the tree branches, protected from intruding ground squirrels and yellow jackets. Around their doorways, the hard, clean-swept red earth resembled a well-worn brick pavement. There is morality in pies.

11 There was a canned provision era, fruitful in sardines and oysters. The canned oysters of those days were as destructive as cannon shot. They penetrated everywhere. In remote and seldom-visited valleys of the Sierras, I have grown solemn over the idea that my footsteps were the first to have ever indented the soil. And then I have turned to behold the gaping, ripped and jagged mouth of one of those tin cylinders scattered like dew over the land, and labeled “Cove Oysters.” One of our prominent officials was once asked what, in the absence of a house or shaft, he would consider an indication of the former presence of miners. He answered: “Empty oyster cans and empty bottles.”

PARAPHRASED

12 I survived all the different eras (periods) of California cookery. The men who swarmed these shores in the gold rush of “49” and “50” did not know how to cook. We knew that bread was made of flour, and that women usually made it. This seemed as natural as sunshine. However, we did not have the knowledge, skill, patience and experience to make bread or anything else.

13 When the first “pork, bean and flapjack” era began, we boiled our pork and beans together for the same length of time. When the beans turned out hard, we wondered why. Then, in the fall of “50,” we learned that beans must be soaked overnight and boiled at least two hours before adding the pork. And what a cheerful thrill a man got when he first successfully turned a flapjack.

14 However, we soon grew tired of wheat cakes. Next came the heavy bread era, which strained our stomachs. For most of us, bread making was a series of disastrous (terrible) failures. Good bread makers, male or female, are born, not made. The bread was either much too light or much too heavy. Our loaves were sour and orange in color, from too much baking soda. Our crust had layers of hardness and thickness, like the layers of the earth.

15 Early in “51” came the era of stewed dried apples. Even now, my stomach shudders as I recall that difficult time. After filling ourselves up with applesauce, we served it to each other, hidden in thick, heavy walls of flour. We struggled with puddings and dumplings. I cannot think of anyone who survived the dried apple era.