Fever 1793

21 The wagon had reached the part of the city where new houses and businesses were under construction. Where there should have been an army of carpenters, masons, glaziers, plasterers, and painters, I saw only empty shells of buildings, already falling into disrepair after a few-weeks of neglect.

22 “Grandfather would not allow it,” I said with confidence. “If Mother is still out in the country, then we two shall care for each other. He doesn’t know the first thing about shopping at the market or cooking, and I need him to chop wood and, and…he will make sure I am well.”

23 “It is good you have each other,” said Mrs. Bowles in the same placid voice. “But you should not leave your house once you arrive. The streets of Philadelphia are more dangerous than your darkest nightmare. Fever victims lay in the gutters, thieves and wild men lurk on every corner. The markets have little food. You can’t wander. If you are determined to return home with your grandfather, then you must stay there until the fever abates.”

24 Grandfather turned to address us. “We may end up at the Ludingtons’ farm after all,” he said. “Josiah here tells me there’s not much food to be found anywhere, Mattie. I’ll write to them again as soon as we arrive home.”

25 ”Won’t do you no good,” the driver interrupted. “The post office just closed down. It could take until Christmas before they can deliver letters.”

26 Mrs. Bowles patted my arm. “Don’t fret, Matilda. If you like, you may choose to take employment at the orphanage. I’m sure the trustees would approve a small wage if you helped with the cleaning or minding the children. They have for Susannah. She’ll help with the laundry.”

27 Susannah didn’t look strong enough to wash a teaspoon, much less a tub full of clothing. “What will happen to her when the fever is over?” I whispered.

28 Mrs. Bowles lowered her voice. “She is at a difficult age. She’s too old to be treated as a child, but not old enough to be released on her own. Her parents owned a small house. The trustees will sell that and use the money for her dowry. We will hire her out to work as a servant or scullery maid. She’s attractive enough. I’m sure she’ll find a husband.”

29 A fly bit the ear of the child on Mrs. Bowles’s lap, and his howl cut off the conversation.

30 Scullery maid, that was one thing I would never be. I imagined Mother’s face when she arrived home and found what a splendid job I had done running the coffee house. I could just picture it—I would be seeing the last customers out the door when Mother would come up the steps. She would exclaim how clean and well-run the coffeehouse was. Grandfather would point out the fancy dry goods store I was building next door. I would blush, looking quite attractive in my new dress—French, of course. Perhaps I could hire Susannah to do the washing up. That would be a way of helping.

31 I broke off my daydream to take in our surroundings. Grandfather and the driver had stopped swapping stories. He turned to look back at me anxiously. We were in the center of a dying city.

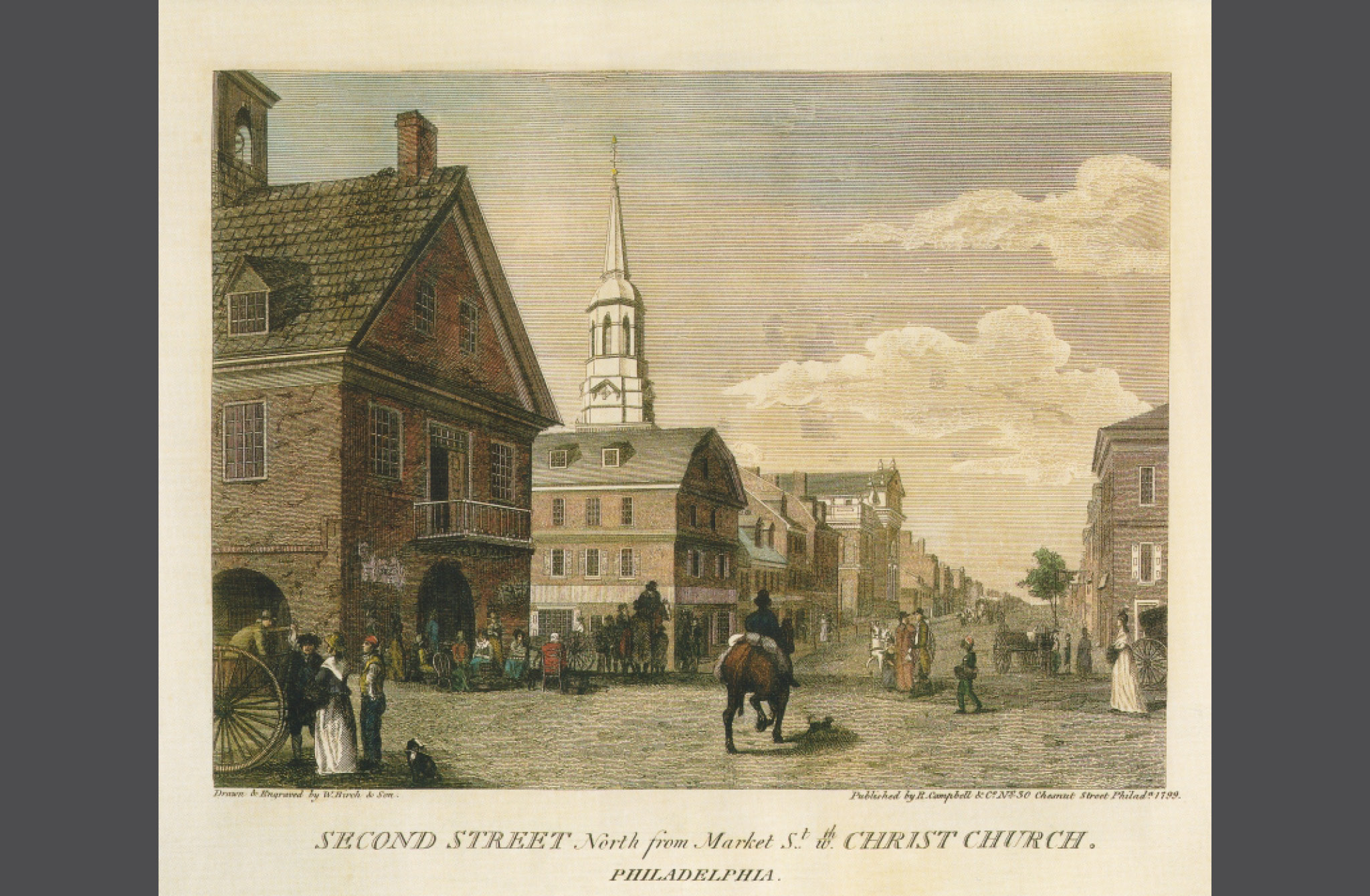

32 It was night in the middle of the day. Heat from the brick houses filled the street like a bake oven. Clouds’ shielded the sun, colors were overshot with gray. No one was about; businesses were closed and houses shuttered. I could hear a woman weeping. Some houses were barred against intruders. Yellow rags fluttered from railings and door knockers—pus yellow, fear yellow—to mark the homes of the sick and the dying. I caught sight of a few men walking, but they fled down alleys at the sound of the wagon.

33 “What’s that?” I asked, pointing to something on the marble steps of a three-story house.

34 “Don’t look, Matilda” said Grandfather. “Turn your head and say a prayer.”

35 I looked. It appeared to, be a bundle of bed linens that had been cast out of an upper window, but then I saw a leg and an arm.

36 “It’s a man. Stop the wagon, we must help him!”

37 ”He is past helping, Miss,” the driver said as he urged on the horses. “I checked him on the way out to fetch you this morning. He were too far gone to go to the hospital. His family tossed him out so as they wouldn’t catch the fever. The death cart will get him soon for burying.

38 I couldn’t help but stare as the wagon rolled by the stoop. He looked about seventeen and wore well-tailored clothes stained with the effects of the fever. Only his polished boots remained clean. His yellow eyes stared lifelessly at the clouds, and flies collected on his open mouth.

39 “Won’t there be a burial, a church service?” I asked as the driver turned east onto Walnut Street.

40 “Most preachers are sick or too exhausted to rise from their beds. A few stay in the square during the day, that takes care of the praying.”

41 How could the city have changed so much? Yellow fever was wrestling the life out of Philadelphia, infecting the cobblestones, the trees, the nature of the people. Was I living through another nightmare?

42 “What date is this?” I asked Mrs. Bowles.

43 “Today is September the twenty-fourth,” she answered.

44 “The twenty-fourth? That’s not possible.” I counted on my fingers. We fled on the eighth: “When we left, there were reports of a thousand dead. Do you know what the total is now?”

45 “It’s double that at least,” she said. “It slowed down those few cool days, but as soon as the temperature rose again, so did the number of corpses.”

46 The driver pulled on his reins to stop the horses. The road was blocked by a line of slow-moving carts, each pushed by a man with a rag tied over his face, each holding a corpse.

47 “The Potter’s Field is ahead,” Mrs. Bowles said as she pointed to the front of the line. “That’s where they’re burying most of the dead. The preachers say a prayer, and someone throws a layer of dirt on top.”

48 Along one side of the square stretched a long row of mounded earth. The grave diggers had dug trenches as deeply as they could, then planted layer after layer fever victims. Some of the dead were decently sewn into their winding sheets, but most were buried in the clothes they died in.

49 “A field plowed by the devil,” I murmured. “They’re not even using coffins.”