Excerpt from Chapter 8 in The Secret of the Yellow Death by Suzanne Jurmain

1 August 31–September 4, 1900

2 Of course, James Carroll had always known that Cuba was full of dangerous diseases. He’d known that coming to the island was a risk. And, yes, the bite from Lazear’s sickly little bug could possibly have given him the fever. But James Carroll had never believed in the mosquito theory. He’d never thought that insects carried the disease. Besides, he couldn’t afford to get the illness. He was a forty-six-year-old married man with five small children to support—and yellow fever often killed people over forty.

3 Still, there was no getting around the fact that his temperature was rising. Something was making him sick. And he needed to know exactly what the illness was.

4 It might be malaria. That could cause high fevers. It was a bad disease; but, still, it could be treated. It wasn’t usually as deadly as yellow fever. Besides, malaria was often found in Cuba. Carroll could have picked up the infection. And the scientist knew there was an easy way of finding out.

5 Early in the morning on August 31, James Carroll dragged himself over to the lab. He jabbed himself with a needle and drew some blood. Then he smeared it on a glass slide and put the slide under the microscope. Carefully, he peered through the eyepiece, focused the lenses, and began to look.

6 For several minutes he scanned the slide. There were plenty of roundish red cells. There were a few irregularly shaped white cells. But no definite sign of malaria—or of yellow fever. The trouble was, that didn’t prove a thing. Diagnosing illness with a microscope was often difficult. Sometimes yellow fever patients had fewer white cells in their blood. But often yellow fever blood looked pretty normal. And malaria? That was tricky, too. Sometimes it was hard to see the tiny organisms that caused the illness in a single drop of blood.

7 Clearly, the microscope wasn’t going to provide a simple answer. And as James Carroll looked up from the eyepiece, he must have known that there was nothing else to do but wait.

8 If it was malaria, he’d know it soon. There would be violent, periodic fevers, vomiting, sores around his lips, and soaking sweats. And if it was yellow fever, well, he’d recognize the bloodshot eyes, the bleeding nose and gums, and the awful yellow skin. One way or another, he’d find out about his illness soon enough.

9 Nobody knows how long Carroll sat in front of his microscope that morning. But he was still there when Lazear and Agramonte walked through the laboratory door—and stared. Carroll looked awful. His face was flushed; his eyes were red. But he tried to joke. The illness was nothing, he said. He’d just somehow “caught cold.”

10 Both doctors begged him to go to bed. Carroll, however, was a stubborn man. As a youngster he’d struggled against poverty. He’d fought to go to medical school. He was used to hardships, and he wasn’t the sort who’d let a little bout of sickness beat him down. Still, finally, he agreed to stretch out on a sofa.

11 It didn’t help. By afternoon, James Carroll was lying in the hospital. At seven p.m. his temperature had reached 102. Soon there was no question about the diagnosis: the scientist had come down with yellow fever.

12 But how could he have gotten the disease? In a state bordering on panic, Lazear and Agramonte reviewed the possibilities.

13 Could it have happened when Carroll visited the autopsy room at Las Animas Hospital in Havana a few days earlier? Could that be where he’d picked up the infection?

14 Or had it happened in the Camp Columbia lab when Carroll let Lazear’s enfeebled little insect bite his arm?

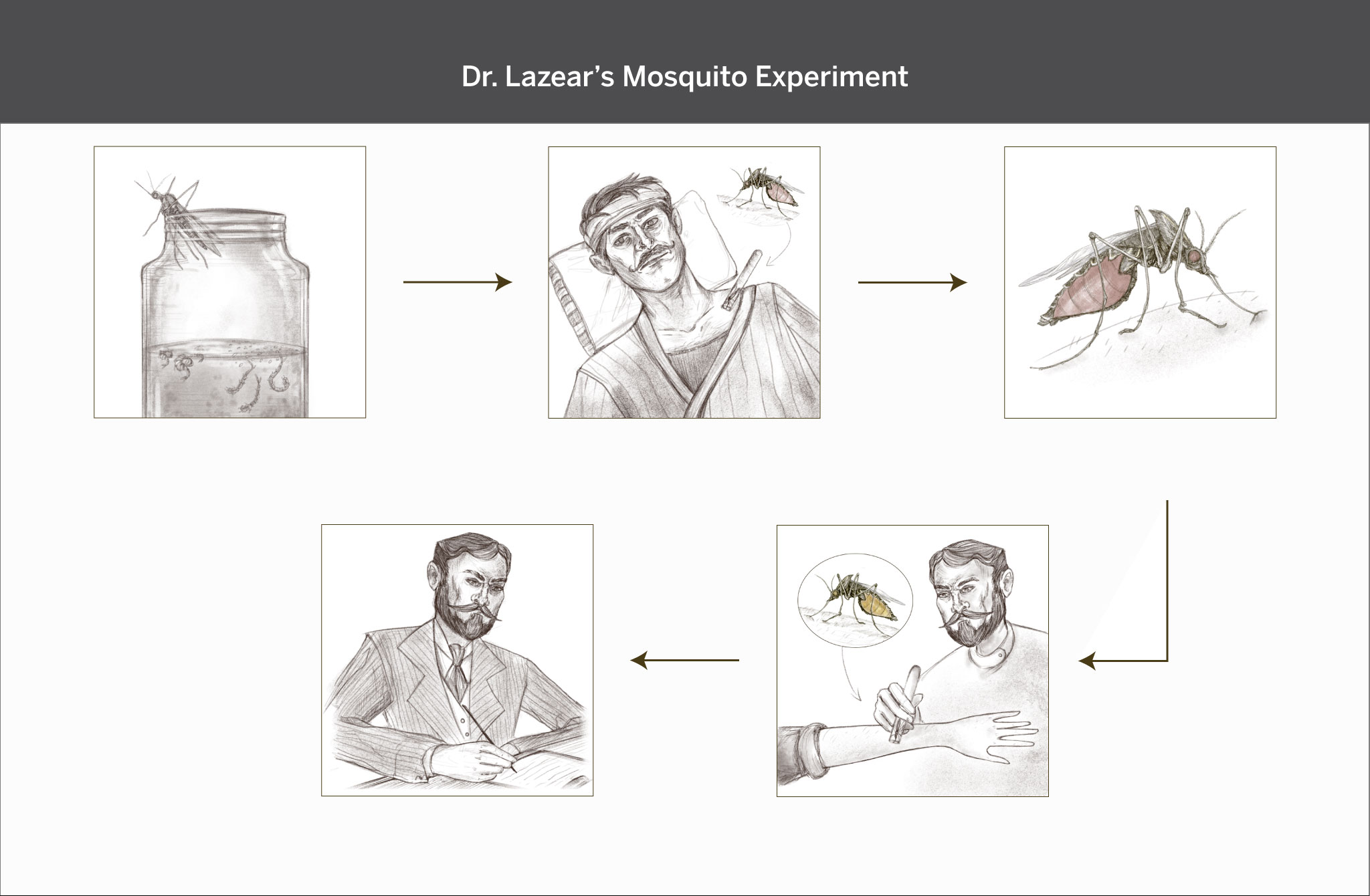

15 Both doctors knew that there was only one good way to find an answer. They would have to let the mosquito that bit Carroll bite another person. Then they would have to see if that victim developed a clear-cut case of the disease.

16 The experiment was basically simple. But to do it, they had to have a healthy volunteer.

17 Agramonte wasn’t a good candidate. There was a chance he’d had a very mild case of yellow fever while growing up in Cuba and now might be completely immune to the disease.

18 Lazear wasn’t a great choice either. He’d already been bitten several times by mosquitoes that had previously bitten yellow fever patients. Since those bites hadn’t made him sick, there was a chance he, too, might actually be immune to the disease.

19 A fresh volunteer would be best.

20 The scientists had barely come to that conclusion when Private William Dean walked by the lab and happened to look in.

21 Dean, a young unmarried man, had just arrived in Cuba. He’d never been near Carroll or any other yellow fever victims, but he had certainly heard a lot about the team’s experiments.

22 “You still fooling with mosquitoes, Doctor?” Dean asked, as he stood in the doorway.

23 “Yes,” said Lazear. ‘Will you take a bite?”

24 “Sure. I ain’t scared of ’em,” Dean replied.

25 Lazear looked at Agramonte. Agramonte nodded. The young private seemed to be the perfect volunteer.

26 Dr. Lazear picked up the tube containing the mosquito that had bitten Carroll. He inverted the tube, pulled out the cotton plug, and placed the opening flat against Dean’s bare arm. The bug flew down, and all three men waited while it settled on the soldier’s skin, inserted its proboscis, and sucked blood.

27 For the next few days, Lazear and Agramonte didn’t tell anyone at Camp Columbia about Carroll’s mosquito bite or Dean’s. Instead, they tried to work. They worried about Carroll, and they wondered privately if young Dean was going to get sick.

28 Carroll himself lay in the hospital, fighting the disease. Roger Ames, the army doctor with the most experience in treating yellow fever, monitored the patient and saw the scientist’s temperature rise to 104. He watched as Dr. Carroll’s skin and bloodshot eyes turned lemon yellow. The sick man’s pulse was slow. His condition was definitely critical, but there was very little Dr. Ames could do. Available drugs like quinine, castor oil, mercury compounds, and opium had no effect on yellow fever. To combat the disease, Ames ordered nurses to keep the patient quiet. He made sure that Dr. Carroll ate nothing while the fever soared but insisted that the scientist sip lemonade or water every hour.

29 At one point Carroll felt a sharp pain in his chest that seemed to stop his heart. Sometimes he babbled feverishly. But experiments were often on his mind. Once, when he ordered his nurse, Ms. Warner, to give the lab mosquitoes a meal of ripe banana, she obligingly obeyed. But when Dr. Carroll said that a mosquito bite had caused his illness, Nurse Warner was seriously shocked. A mosquito causing yellow fever? Why, everybody knew that Finlay’s theory was a joke. The whole idea was crazy, and, before she went off duty, Ms. Warner had formed her own opinion of the sick man’s silly statement. “Patient delirious,” she note briefly on the chart.