A reality TV show will send volunteers to colonize Mars.

Excerpt: “Life on Mars to Become a Reality in 2023, Dutch Firm Claims” from The Guardian

Author: Karen McVeigh

1 Published: April 22, 2013

2 A few months before he died, Carl Sagan recorded a message of hope to would-be Mars explorers, telling them: “Whatever the reason you’re on Mars is, I’m glad you’re there. And I wish I was with you.”

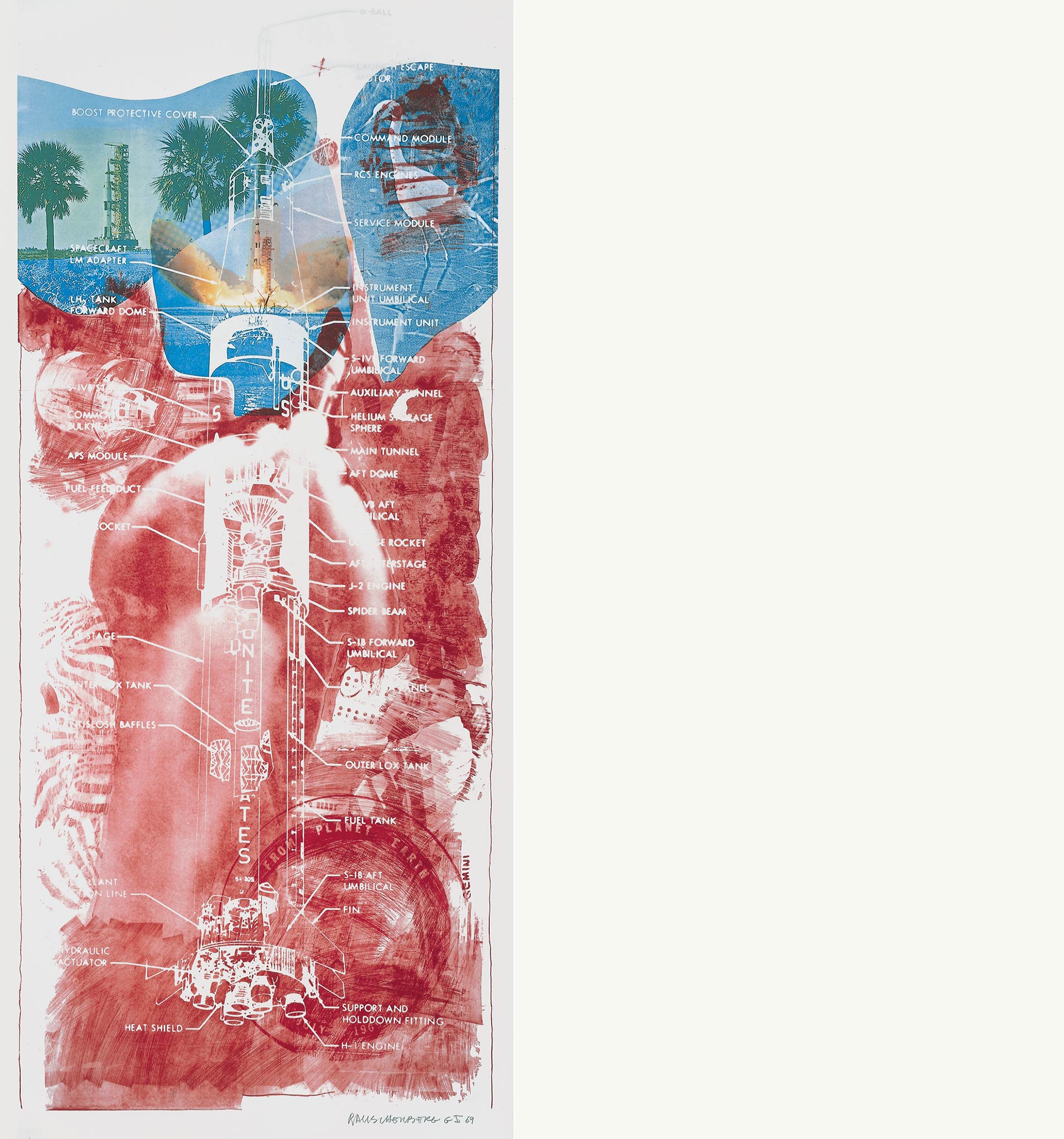

3 On Monday, 17 years after the pioneering astronomer set out his hopeful vision of the future in 1996, a company from the Netherlands is proposing to turn Sagan’s dreams of reaching Mars into reality. The company, Mars One, plans to send four astronauts on a trip to the Red Planet to set up a human colony in 2023. But there are a couple of serious snags.

4 Firstly, when on Mars their bodies will have to adapt to surface gravity that is 38% of that on Earth. It is thought that this would cause such a total physiological change in their bone density, muscle strength and circulation that voyagers would no longer be able to survive in Earth’s conditions. Secondly, and directly related to the first, they will have to say goodbye to all their family and friends, as the deal doesn’t include a return ticket.

5 The Mars One website states that a return “cannot be anticipated nor expected”. To return, they would need a fully assembled and fuelled rocket capable of escaping the gravitational field of Mars, on-board life support systems capable of up to a seven-month voyage and the capacity either to dock with a space station orbiting Earth or perform a safe re-entry and landing.

6 “Not one of these is a small endeavour” the site notes, requiring “substantial technical capacity, weight and cost”. . . .

7 The prime attributes Mars One is looking for in astronaut-settlers is resilience, adaptability, curiosity, ability to trust and resourcefulness, according to Kraft. They must also be over 18.

8 Professor Gerard ’t Hooft, winner of the Nobel prize for theoretical physics in 1999 and lecturer of theoretical physics at the University of Utrecht, Holland, is an ambassador for the project. ’T Hooft admits there are unknown health risks. The radiation is “of quite a different nature” than anything that has been tested on Earth, he told the BBC.

9 Founded in 2010 by Bas Lansdorp, an engineer, Mars One says it has developed a realistic road map and financing plan for the project based on existing technologies and that the mission is perfectly feasible. The website states that the basic elements required for life are already present on the planet. For instance, water can be extracted from ice in the soil and Mars has sources of nitrogen, the primary element in the air we breathe. The colony will be powered by specially adapted solar panels, it says.

10 In March, Mars One said it had signed a contract with the American firm Paragon Space Development Corporation to take the first steps in developing the life support system and spacesuits fit for the mission.

11 The project will cost a reported $6bn (£4bn), a sum Lansdorp has said he hopes will be met partly by selling broadcasting rights. “The revenue garnered by the London Olympics was almost enough to finance a mission to Mars,” Lansdorp said, in an interview with ABC News in March.

12 Another ambassador to the project is Paul Römer, the co-creator of Big Brother, one of the first reality TV shows and one of the most successful. . . .

13 The aim is to establish a permanent human colony, according to the company’s website. The first team would land on the surface of Mars in 2023 to begin constructing the colony, with a team of four astronauts every two years after that.

14 The project is not without its sceptics, however, and concerns have been raised about how astronauts might get to the surface and establish a colony with all the life support and other requirements needed. There were also concerns over the health implications for the applicants.

15 Dr Veronica Bray, from the University of Arizona’s lunar and planetary laboratory, told BBC News that Earth was protected from solar winds by a strong magnetic field, without which it would be difficult to survive. The Martian surface is very hostile to life. There is no liquid water, the atmospheric pressure is “practically a vacuum”, radiation levels are higher and temperatures vary wildly. High radiation levels can lead to increased cancer risk, a lowered immune system and possibly infertility, she said.

16 To minimise radiation, the project team will cover the domes they plan to build with several metres of soil, which the colonists will have to dig up.

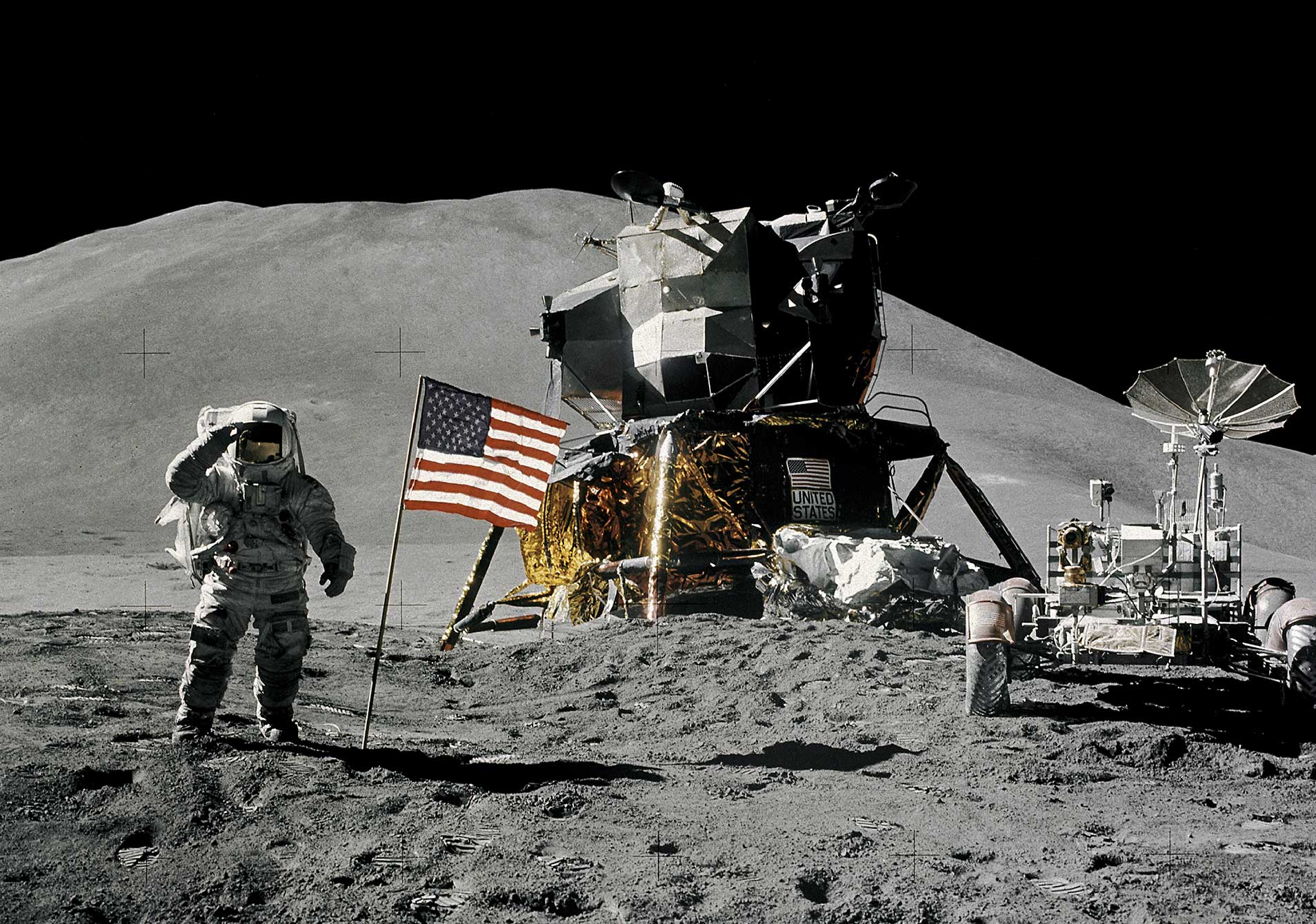

17 The mission hopes to inspire generations to “believe that all things are possible, that anything can be achieved” much like the Apollo moon landings.

18 “Mars One believes it is not only possible, but imperative that we establish a permanent settlement on Mars in order to accelerate our understanding of the formation of the solar system, the origins of life, and of equal importance, our place in the universe” it says.

19 The longest anyone has ever spent in space is 438 days, achieved by Valeri Polyakov, of Russia, in a manned space flight in 1994.

20 But the Mars One website states: “While a cosmonaut on board the Mir was able to walk upon return to Earth after 13 months in a weightless environment, after a prolonged stay on Mars the human body will not be able to adjust to the higher gravity of Earth upon return.

21 “There is a point in time after which the human body will have adjusted to the 38% gravitation field of Mars, and be incapable of returning to the Earth’s much stronger gravity. This is due to the total physiological change in the human body, which includes reduction in bone density, muscle strength, and circulatory system capacity.”